VISIT

MUSEUM STORE

MEMBERSHIP

OZ NEWS

CONTACT

VISIT

MUSEUM STORE

MEMBERSHIP

OZ NEWS

CONTACT

DISCOVERING OZ: THE ROYAL HISTORIES -- A COMIC “PATCHWORK GIRL” REOPENS THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD!

DISCOVERING OZ: THE ROYAL HISTORIES --

A COMIC “PATCHWORK GIRL” REOPENS THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD!

by John Fricke

[Above: The embossed cloth cover of the first edition of THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ (1913) carried a different John R. Neill design than that shown here. (You can see the cloth cover in this month’s Vlog; please scroll down to July 7th on The OZ Museum Facebook page and click on the link there!) Meanwhile, the colorful Neill illustration “up top” graced the front panel of the book’s original dust jacket. It was later used as a paste-down cover label when the stamped design was abandoned circa 1930.]

[A BRIEF, PRELIMINARY NOTE FROM JOHN: The rough draft text and art selection attendant to this “THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF OZ” Blog were basically wrapped up nearly two months ago. Then I was hit with sciatica (!), and everything went on hold here, as I figuratively “tread water,” went AWOL for seven weeks of physical therapy, and recovered. 😊 Blessedly, all is fine and well again now, and I sincerely apologize for the delay in this posting!]

While launching the latest episode of a continuing radio series, announcers used to breathlessly proclaim things like, “When last we left our stalwart and valiant hero . . . .”

Well, we’ll just expand upon that here by explaining: In 1910, “our stalwart and valiant hero,” author L. Frank Baum, very publicly declared that he’d written his final Oz story. THE EMERALD CITY OF OZ was IT for him, and he intentionally walked – pretty much cantered -- away from what had never been meant to become a fantasy SERIES. He also used that sixth and final volume to announce that, through the sorcery of Glinda the Good, his magic kingdom had become invisible and inaccessible to everyone from the Great Outside World. Even he could no longer communicate with Oz.

In truth, Baum had grown somewhat tired of his creation and characters, and he wanted to write other fairy tale novels for children. Fulfilling that desire, he published THE SEA FAIRIES in 1911 and SKY ISLAND in 1912; both tales were admirable and well-received. At a time he could ill afford It, however, those volumes sold barely half as many copies as had each new Oz book. Pretty much concurrently (circa 1909), his long-term royalties from THE WIZARD OF OZ stage musical came to an end, after that musical’s seven enriching seasons on the boards.

It was a calamity all around, as Baum was also being crushed by debts incurred by his multi-media FAIRYLOGUE AND RADIO-PLAYS lecture tour of 1908. He served as the show’s onstage, charismatic host/elocutionist, and both he and the ingenious program were enthusiastically and genuinely well received. Yet the production – including silent, hand-colored film clips, color slides, and full orchestra accompaniment -- had been prohibitively expensive to produce and cart around the country; the RADIO-PLAYS closed after only three months. Baum’s creditors waited a year and then another, but by 1911, the entrepreneur was forced to declare bankruptcy.

[Above top: Baum’s 1908 RADIO-PLAYS presented sequences and scenes from his OZ and JOHN DOUGH AND THE CHERUB books. The author poses here with thespians who appeared in the “movie” portion of the financially unsuccessful touring production. Above bottom: The beautiful endpapers for THE SEA FAIRIES, Baum’s first post-Oz fantasy, were illustrated (as was the entire edition) by John R. Neill. Between 1904 and 1910, Neill had pictured six Baum titles, including five Oz books. Yet even with his superb artwork, he couldn’t envelop or provide Baum’s new protagonists, Trot and Cap’n Bill, with the requisite, long-established “Oz appeal.” The little California girl and her grizzled old sailor companion are shown here after being transformed into mermaids, so as to best enjoy their excellently presented undersea adventures and accompany their tour guide.]

Thus, by early 1912, Baum and publishers Reilly & Britton had already begun elaborate plans for the writer to “return to Oz” in a major manner a year later. He was – true to the tradition of more than a decade -- being swamped with thousands of letters from children requesting more Oz stories. Consequently and cleverly, he would credit a suggestion from one of them with the idea that he circumvent Glinda’s impenetrable barrier by communicating with the Emerald City by the “wireless” telegraph. In that way, he could once again receive and share the latest news from Dorothy and all.

Adopting that concept, Baum enthusiastically began to write what would be his longest Oz book, THE PATCHWOK GIRL OF OZ. His two new “star” creations were the wildly comical, original title character, and her companion, Ojo, a little Munchkin boy. Near the onset of the story, the lad’s only relative -- cherished, aged Unc Nunkie -- is accidentally, magically turned into a marble statue. The plot of the book thus evolves: the child and the cotton-stuffed miss have the task of traveling Oz, as (in company with newly acquired friends) they search for the ingredients required to concoct a compound to bring the old gentleman back to life.

[Above top: The Patchwork Girl, affectionately nicknamed Scraps, makes a carefree leap, as Ojo looks on from the far side of a Munchkin Country brook. Made of an old quilt, the ebullient, lackadaisical creature was brought to life by a magical power devised by the famous Dr. Pipt; he intended that she serve as a maid for his wife, Margolotte. Above bottom: Ojo and his Unc happen to turn up at the cottage of the Pipts just prior to the application of the life-giving powder to the padded heroine. The child wisely suggests that Margolotte add something from the doctor’s cabinet of granulated brains to Scraps’ stuffing. Moments later -- surreptitiously and on his own -- Ojo adds an abundance of extra cleverness and multiple other qualities (including poesy) to the mix! In this way, and as soon as she’s alive, Scraps becomes eminently worthy of the thought-provoking challenges ahead of her in THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ. As well, she frequently comes forward with nonsense rhymes, enhancing countless adventures to come.]

Ojo is the first boy in nine years to predominantly feature in one of Baum’s Oz books. (He was preceded by Tip in THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ in 1904.) Though sometimes brought to tears by the ongoing fear of losing his lifelong and only companion to statuary, the child is stalwart enough and willing to risk anything to achieve his uncle’s recovery. In addition to Scraps, he’s aided at various times in his cross-country search of Oz by numerous others: a) an earlier Pipt creation, the ludicrously self-absorbed, see-through-and-through Glass Cat; b) a sought-after-and-met-enroute curiosity, the Woozy; and c) several famous Ozians of past renown and history: the Shaggy Man, the Scarecrow, Toto, and little Dorothy herself.

[Above top: A legendary (if physically crooked) magician, Dr. Pipt is shown here in the process of creating his most famous potion. It requires the simultaneous stirring of four kettles for six years to distill the ingredients that will boil down to generate the particles of the Powder of Life. When, as planned, it brings Scraps to manic existence early in Baum’s story, the girl inadvertently jostles a bottle of the doctor’s Liquid of Petrification on an upper shelf, splattering it on Ojo’s uncle and Margolotte. Rather than depend on six more years of stirring to create the antidote to bring the two back to life, Dr. Pipt sends Ojo out to recover the components for an immediate cure. Above left: Ceaselessly boastful of her heart and brains (“you can see ’em work!”), the Glass Cat reaches new heights of self-adoration in THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ. Above right: One of Baum’s merriest and nicest discoveries, the Woozy is outstandingly loyal and superlative company on the first segment of Ojo’s journey to the Emerald City. His importance to the saga itself is revealed in the next paragraph.]

Since you’ve met the Woozy in the caption and art above, it’s time now to suggest you notice his distinctive and idiosyncratic physical qualities – especially as they importantly figure into THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ quest. Ojo seeks out the genial beast in the first place, simply because of the three hairs at the tip of his tail; these strands are one of five essential elements required to counteract the Liquid of Petrification. They’re visible in the Neill portrait above, and just below, you can see the little square oddity as he willingly volunteers to part with them for Ojo’s sake. When they won’t yield, the Woozy perkily joins his tug-of-war participants on their excursion to find the remaining four curative components, so that Ojo will at least have the three hairs in his possession when Dr. Pipt needs to access them for medication preparation. (At the conclusion of this paragraph – and following the image of the struggle for the Woozy’s decorative “fringe” -- Ojo’s discovery of three of the other ingredients are pictured as well: 1) The intrepid youngster also retrieves a gill of water from a dark well – one that has never seen any light whatsoever. 2) He achieves what he’d imagined might prove an impossible task by gaining “a drop of oil from a live man’s body.” 3) Finally, he picks a rare six-leaf-clover from the greensward grounds of the Emerald City. The latter action brings arrest and shame to the child; there is an excellent, lightly philosophical conversation with his convivial jailor in this section of the book, all about the regulations and procedures of the Oz penal system. It might be easily grasped and profitable for a young reader or listening audience.)

In the course of his efforts, Ojo next encounters a trial (and beneficence) under the jurisdiction of Princess Ozma. He and Scraps are then joined by Dorothy, Toto, and the Scarecrow to seek (in the Winkie and Quadling Countries of Oz) the vital magic makings as shown above. Such successes on the trip are interspersed with various diverting, droll, or threating Baum/Ozian tests and confrontations. The explorers settle a war between the mountain-dwelling Horners and Hoppers -- so-named as they, respectively, boast either a horn in the middle of their foreheads or possess “but one leg, set just below the middle of” their fat round bodies and upon which they easily and swiftly hop around. Scraps and her companions also confront (and escape, if barely) “Mister Yoop: The Largest Untamed Giant in Captivity” – and only a recap of much of the rest of Baum’s own description can do him justice:

Height, 21 feet. – (And yet he has but two feet.)

Weight, 1640 Pounds. -- (But he waits all the time.)

Age, 400 Years ‘and Up’ (as they say in the Department Store advertisements.)...

Appetite, Ravenous -- (Prefers Meat People and Orange Marmalade.)

STRANGERS APPROACHING THIS CAVE DO SO AT THEIR OWN PERIL!

P.S. -- Don’t feed the Giant Yourself.

Even an anticipated quiet raft ride on a waterway between the Quadling and Winkie Countries presents distinctive obstacles: the quintet literally and figuratively comes up against a self-reversible river and wall of water. As illustrative proof of all these claims, here are Neill’s splendid evocations of Hip Hopper (champion wrestler of his realm), Mr. Yoop (“at home”), and the barricade of flowing H2O:

Against all such odds (and as noted and “Neill’d” above), Ojo & Company manage to gather four of the five necessary ingredients for Dr. Pipt’s swift remake of the Powder of Life. They’re then, however, brought up short by the most gentle-hearted of all the Oz characters. He, for a sacred and unassailable reason, won’t provide them with the final element they require; you’ll have to read the book to find out who and why! This, however, is where the supreme magic of the Wizard of Oz himself comes into play -- and as Scraps finds a new and permanent home in the Emerald City, Ojo and his uncle are at last and gratefully reunited:

THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ is one of the liveliest, most engaging, and most expeditiously moving of all Baum Oz histories. Truth be told, the brief [!] summation above only does justice to a percentage of its escapades and characters. Omissions here include annotation of the reunions with such Oz mainstays as Billina, Jack Pumpkinhead, the Tin Woodman, the Guardian of the Gates, the Soldier With the Green Whiskers, the Cowardly Lion, and the Hungry Tiger; a singular visit with the Foolish Owl and the Wise Donkey; chance meetings with the Tottenhots, a Giant Porcupine, a living phonograph, an optical illusion gate and fence, gigantic carnivorous plants . . . and more. Given the author’s story-telling genius, however, it all soars by in masterful fashion; Baum was a great entertainer!

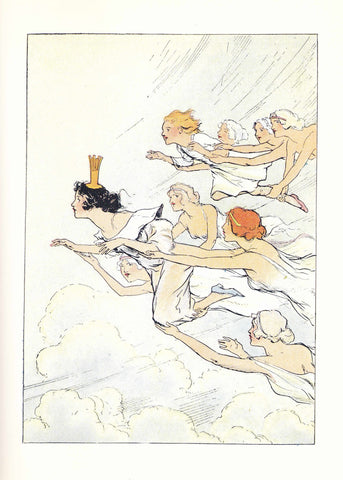

The “Royal Historian” was, of course, once again aided in his triumph (and climb back to a swift, strong-selling presence in the marketplace) by his illustrator and publisher. Neill brought renewed spark, energy, and especially humor to his picturizations of the latest Oz “cast members” – as it’s hoped can be seen throughout this Blog. He was much supported in his work by the lavish mounting Reilly & Lee provided for the seventh Oz book. They forsook the traditional sixteen inserted color plates of some of the preceding series titles, and instead used full color on many of the full-page drawings and chapter heads throughout. These were augmented by additional black-and-white Neill graphics; the final result provided alternately gleeful or fascinating images on page after page.

Additionally, the publishers widely and rapturously advertised Baum’s Ozzy comeback; they even separately issued his six LITTLE WIZARD STORIES -- abbreviated tales about the most celebrated Ozites. These, too, were colorfully illustrated by Neill. The miniature booklets hit the market just prior to THE PATCHWORK GIRL and served as a sort of trailer or preview of Baum’s coming magnum opus. (A year later, in 1914, Reilly & Lee gathered the six stories into a book of their own; the cover of that edition and one of the early announcements about THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ are shown here:)

The waiting juvenile audience provided delighted response to Baum’s latest news updates from Oz, and their joy was heartily seconded by the press. The Tacoma (Washington) NEWS exclaimed of Scraps, “[She] is probably the most unique character creation from Mr. Baum’s pen. She represents the spirit of this day and age, and is quite the liveliest girl ever put into a story . . . illustrated in a wonderful way by . . . Neill.” Defining Baum as “the prince of story tellers for the little folk and even their parents,” the Grand Rapids (Michigan) HERALD made the forthright declaration that “there is only one who can tell” the Oz stories. THE PUBLISHERS’ WEEKLY defined the book as both “exciting” and “thrilling,” and the Los Angeles TIMES decided that THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ “is brimming with humorous situations and keen wit from cover to cover. That’s why the grown-ups will appreciate it. And as to the kiddies . . . they will find [the book] just one grand whirlwind of joy.”

Baum had again and indeed slipped into high gear. He tentatively planned on turning Scraps and her exploits into a stage musical comedy. Instead, the story became the basis for the first production of his own Oz Film Manufacturing Company. THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ hit screens (what screens there were, anyway) in 1914. In the artwork below, you’ll see one of the announcements to the motion picture industry about this feature-length movie, as well as two stills in which Scraps (teenage French acrobat/gymnast Pierre Couderc) has her initial meetings with the Woozy (animal impersonator Fred Woodward) and the Scarecrow (Herbert Glennon). The flirtation of the cotton-stuffed girl and the man of straw – pretty much directly transposed from Baum’s text to the screen – is a highlight of both book and movie!

Unfortunately, there was no audience in 1914 for what would now be termed “family entertainment,” and the Oz Film Company’s few projects – while well done – failed to find an audience. As a result, the ever-ground-breaking Baum also saw the failure of his attempt at tie-in merchandising The little wooden Woozy he hoped would entice the imaginations and consumers of the country barely survived preliminary promotion; the excessive number of remaining toys were, according to legend, later used as kindling in the various Baum homes. (One of the lone survivors is show below.)

Most importantly, however, the Baum/Neill/Reilly & Britton THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ firmly established the concept of an annual, new Oz book, a tradition that continued for thirty years. From 1913 through 1942, there was a fresh title available every Christmas or December holiday, or for a birthday present or vacation trip, or as a reward or general gift. Scraps became an immediate and ever-after favorite among all the other foremost Ozzy celebrities, and she again figured prominently in such ensuing titles as THE LOST PRINCESS OF OZ and GLINDA OF OZ (by Baum); THE GNOME KING OF OZ and OJO IN OZ (by Ruth Plumly Thompson), THE WONDER CITY OF OZ (by John R. Neill), and THE MAGICAL MIMICS OF OZ (by Jack Snow). Decades later, Neill’s daughters enlisted Eric Shanower -- modern-day-yet-traditionalist Oz artist/author supreme – to illustrate Scraps as the title character (and to edit the manuscript) of their father’s unpublished THE RUNAWAY IN OZ. Neill had died suddenly in 1943, before he could polish the story or do much of the art; even fifty years later, Eric was the ideal choice to step in. He employed his own magic and gifts to finish a glorious “new” Oz book about the Patchwork Girl and her madcappery, and Books of Wonder in New York made of it a stunning publication in 1995.

Meanwhile, Baum’s own 1914 THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ is one of many Oz titles that have been translated and published abroad. The 1977 Hayakawa edition from Tokyo is shown below (its illustrations by Sonoko Arai). Also of interest is the gigantic 1988 coloring book of the story, issued by Colorful Fund Raising, Inc. of Plainfield, NJ, with new pictures by Vern Henkel. Finally – and building to the best, of course -- you’ll see THE RUNAWAY IN OZ cover image. (Copyright © 1995 Eric Shanower. All rights reserved.)

The eccentricities manifested and enjoyed by the Patchwork Girl also have led to ongoing interest in dramatic adaptations of her scrapes and verses. There have been plays, musicals, and ballets incorporating the Scraps saga or character, and she’s at least twice been seen in video or film incarnations. In 1957-58, Walt Disney seriously considered starring “The Mouseketeers” from TV’s hugely popular THE MICKEY MOUSE CLUB in an original film musical, THE RAINBOW ROAD TO OZ. A September 1957 episode of DISNEYLAND presented three semi-produced numbers from the proposed picture. Although the movie itself was eventually abandoned, kinescopes of the songs from the TV show remain. One of them featured Scraps and the Scarecrow (Doreen Tracey and Bobby Burgess) in an extended routine called “Patches”; there’s a photographic glimpse below. Almost thirty years later, Disney’s company produced a feature-length, murky RETURN TO OZ (1985), whose many plusses were swamped by a mostly humorless script and a dark approach to Baum and his fantasies. The “all-star” finale trotted out a score of Oz stars (though they were not part of the movie story itself); fortunately, Scraps stood still off-camera long enough to be captured for posterity:

Whatever the vagaries of her history, however, it was Scraps who brought Oz back to the public – exactly one-hundred-and-ten-years ago. She’s been an unquestioned shining light in the pantheon ever since. Take a look, please, at Neill’s depiction of her original, initial meeting with the Scarecrow; the impressed adulation on his face represents the reverence of many – for her jollity and rhyming and sauce and sassiness and savvy.

It is most certainly some of her own personal appeal and attractiveness that spiritually contributed to L. Frank Baum’s return to Oz. He was going there anyway, of course, but there’s no question that she helped light the way. And from that moment on, for the rest of his life, he never again left his “homeland.”

Meanwhile, countless numbers of us who’ve traveled there, companioning with Scraps and all across the decades, have never left, either!

And – most gratefully -- Oz has never left us. 😊

Article by John Fricke